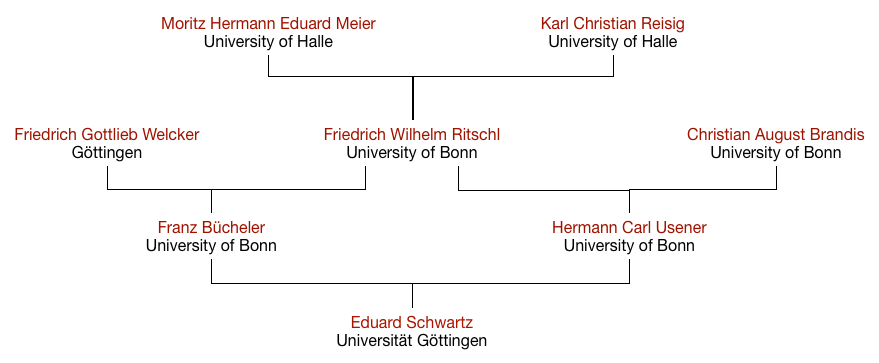

This is the second part of my reconstruction of my academic lineage, in which we encounter someone whose dissertation defense lasted seven hours and someone else who basically compiled his dissertation the night before it was due.

I am still learning quite a bit about each of these academic ancestors of mine, but because this could take a while, I wanted to present at least the outlines of the tree and give a few notes on the characters in it.

In the first part, we reached Eduard Schwartz, who defended his dissertation in 1880 in Bonn and who worked with two advisors, Franz Bücheler and Hermann Usener. Before we go further, I have to note that with Schwartz, there’s a blemish in my academic ancestry: Wikipedia says that in 1928, Schwartz became a supporter of the antisemitic Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (although they also report that he had no sympathy for the Nazis). We’ll soon see that there is a modicum of anticipatory redemption earlier in the tree.

Bücheler & Usener

Usener and Bücheler were the twin towers of classical philology in Bonn, lifelong friends, and jointly advised plenty of other students besides Schwartz. Here are pictures of them:

With them, the tree branches in an interesting way. Bücheler and Usener both got their degrees in Bonn (Bücheler in 1856 at the age of 18 (!) and Usener in 1858 at the age of 24). Both of them had two advisors, as far as I can tell, and they shared one of them.

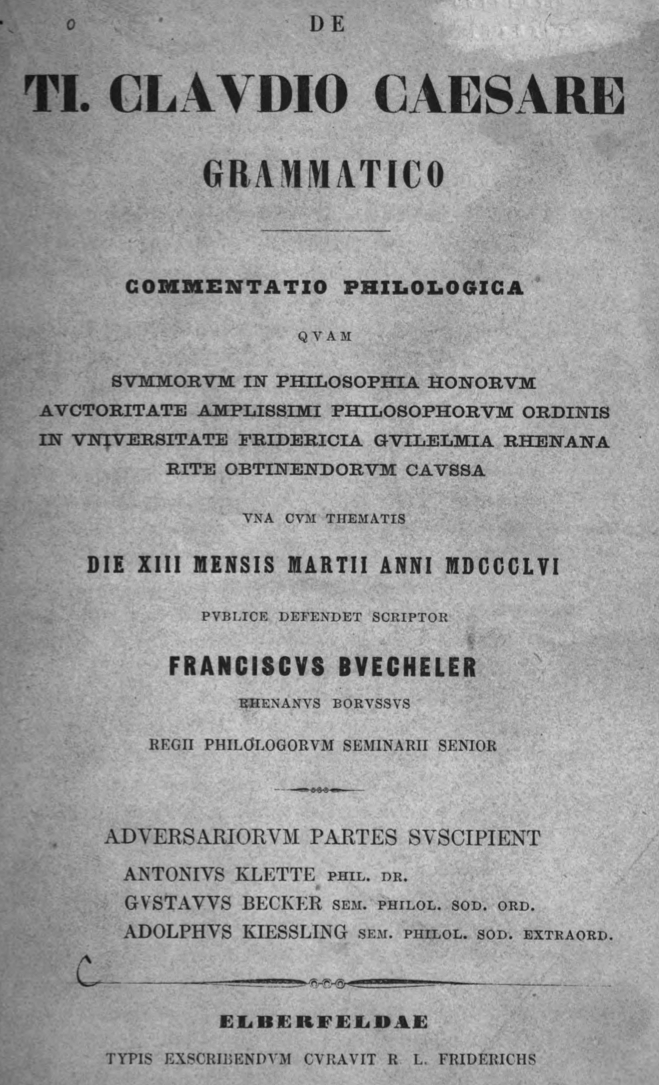

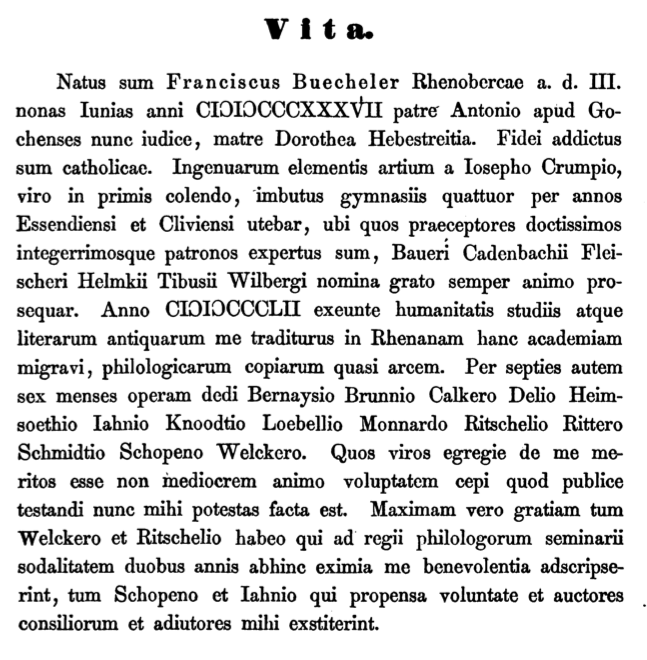

Franz Bücheler (* 3. Juni 1837 in Rheinberg; † 3. Mai 1908 in Bonn) graduated on March 13, 1856 in Bonn with a dissertation entitled “De Ti. Claudio Caesare Grammatico” (freely downloadable from Google), which deals with Latin orthography during the time of Emperor Claudius. He lists as advisors Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker and Friedrich Ritschl. Here are the title page and the vita from his dissertation:

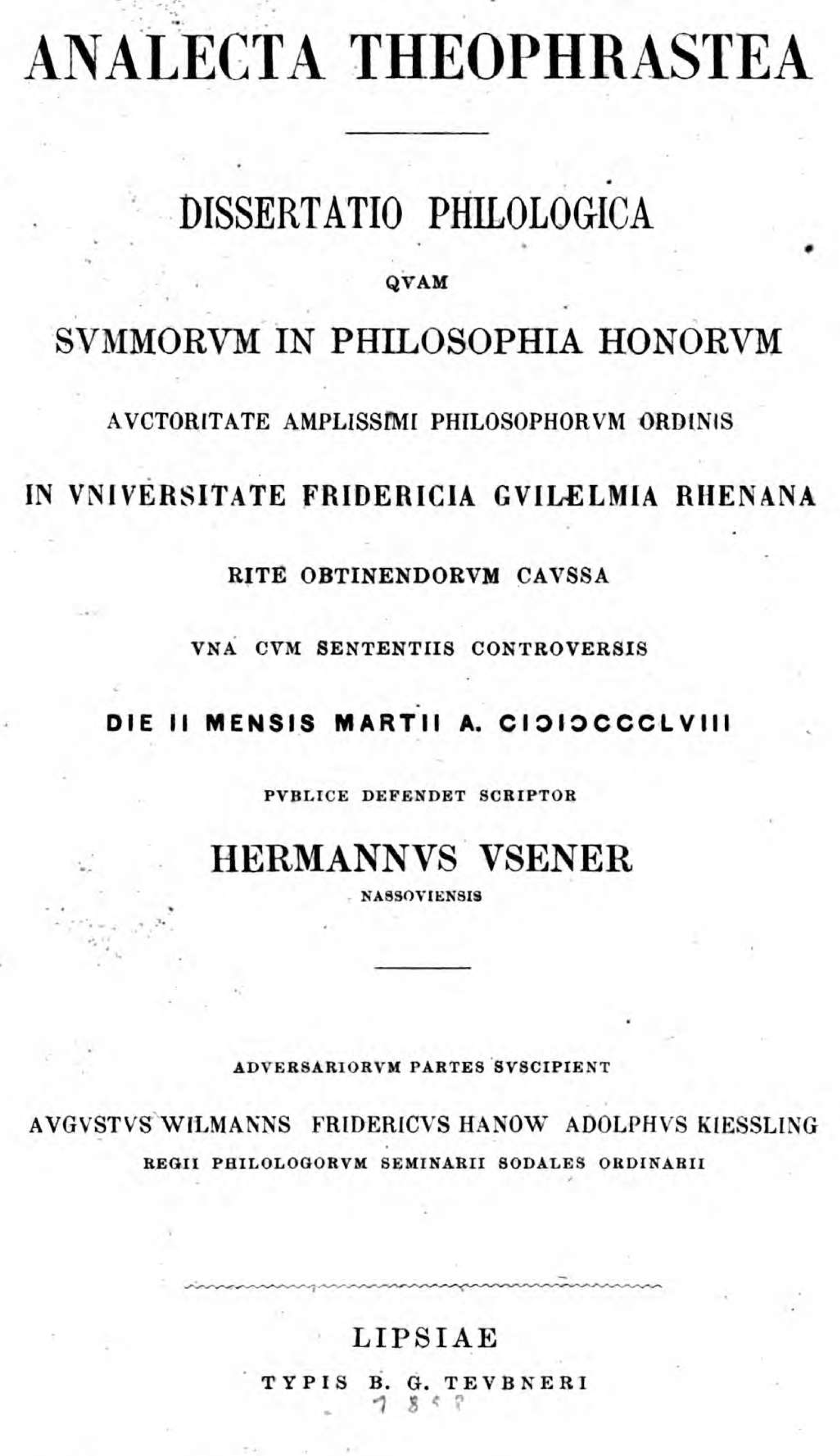

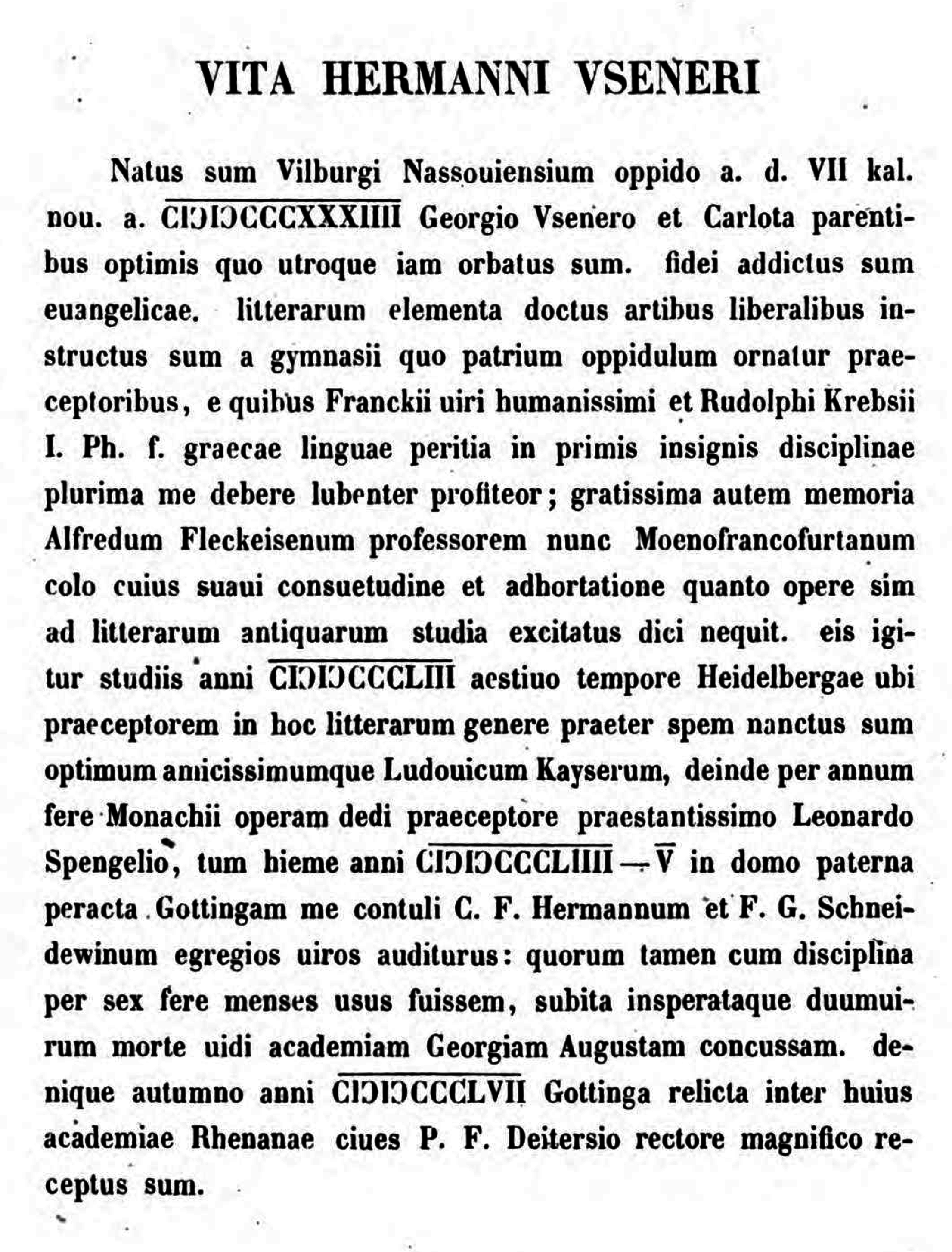

Hermann Carl Usener (* 23. Oktober 1834 in Weilburg; † 21. Oktober 1905 in Bonn) wrote a dissertation called “Analecta Theophrastea” (freely viewable and downloadable from the library in Munich). He dedicates the work to his two main teachers: Christian August Brandis and, again, Friedrich Ritschl. Here are the title page, dedication, and vita from the dissertation:

The Bonn-centrism of this period of our genealogy is both personally appropriate (given my years in nearby Cologne and my frequent visits to Bonn) and historically non-accidental: Bonn was a pre-eminent center of classical philology. A history of the University of Bonn points out the two successive triumvirats of classical philology that taught in Bonn: Usener, Bücheler, and Kekulé, and before them, Welcker, Ritschl, Jahn. The author claims that these six would have to be mentioned among the twelve most important scholars in classical studies during the 19th century. In fact, Wilamowitz is quoted as saying that the history of classical philology simply is the history of Bonn’s philological seminar.

Continuing from Usener and Bücheler, there are now three ancestors to look at: Brandis, Welcker, and Ritschl. Brandis and Welcker had no doctor father that I can identify, so only Ritschl’s branch of the tree continues into the past.

Brandis

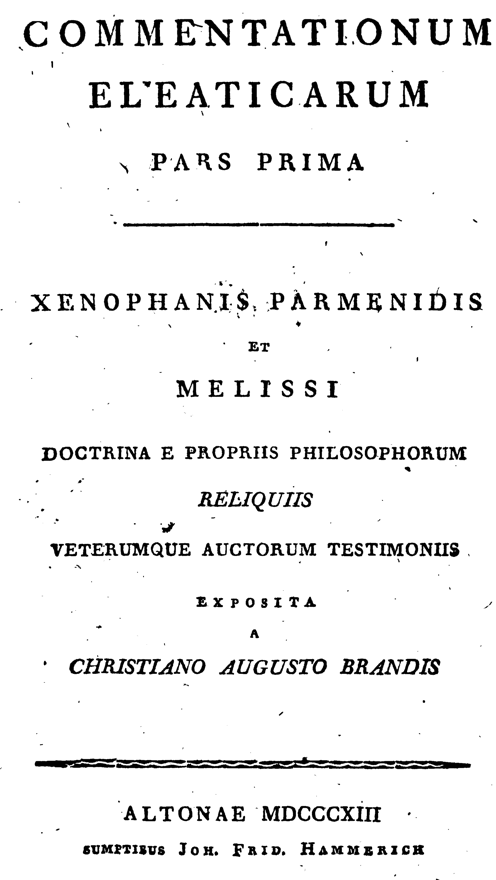

Christian August Brandis (* 13. Februar 1790 in Holzminden; † 21. Juli 1867 in Bonn) graduated on January 12, 1812 (at the age of 21) at the University of Copenhagen, with a thesis “Commentationes Eleaticarum” (a collection of fragments from Xenophanes, Parmenides and Melissus). He had studied at the University of Kiel before, starting at the age of 18 (so it took him little more than 3 years to get his first degree). Brandis doesn’t seem to have had a clear advising relationship with anyone. I haven’t found out who, if anyone, might have been his sponsor in Copenhagen. Even his autobiographic sketch doesn’t include any mention of teachers or advisors in Copenhagen, just a list of people he hung out with. He does say that his defense lasted seven hours, so maybe that left such a scar that he repressed the memories. In any case, unless I manage to find out more, this branch of the tree ends with Brandis. Here is the title page of his thesis:

There is no vita or dedication in the thesis.

Welcker

Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker (* 4. November 1784 in Grünberg; † 17. Dezember 1868 in Bonn) studied classical philology at the University of Giessen. He had to earn his keep by teaching at a kind of prep school and in his free time wrote his dissertation “Exercitatio philologica imaginem Ulyssis quae in Iliade exstat adumbrans”, which got him his doctorate two days before Christmas 1803 (when he was barely 19 years old). (I have not been able to access the work.) Welcker was home-schooled as a youth and seems to have continued mainly as an autodidact, so just like with Brandis, the tree ends with his node.

In something of an anticipatory redemption for the academic family, he was a notorious liberal and was arrested at least once.

Welcker was house teacher and friend in the Humboldt household when they were in Rome. He wrote a history of Greek gods and Mommsen said of him that the gods wouldn’t let him die before he had finished writing their history; he lived to the ancient age of 84. He was director of Bonn’s university library for 35 years.

I should note that another of Welcker’s students, Friedrich Christian Dietz, has massive progeny among modern linguists, since Uriel Weinrich and through Weinrich, William Labov, are among his decendents. See the relevant subtree here. So, all of the people tracing back their ancestry to Dietz are distant cousins of ours.

Ritschl

Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl (* 6. April 1806 in Großvargula (Thüringen); † 9. November 1876 in Leipzig) got his degree at the University of Halle in 1829 (at the age of 23). He taught at various universities but for the longest time in Bonn. He is the founder of the Bonn School of Classical Philology and thus was perhaps the true ancestor of Usener, Bücheler, Schwartz, von der Mühll, and Theiler, and thus of Egli, Kratzer, and myself. To see the topics that he covered in his teaching, we can inspect the list of all of the classes he taught when he was at the University of Leipzig from 1866 to 1876.

His most famous student is Friedrich Nietzsche, who he taught in Bonn and Leipzig, and who he helped to his first professorial appointment, in Basel, which Nietzsche got without having written a dissertation. Thus, through Ritschl’s mentorship of Nietzsche, my academic family has acquired a truly illustrious cousin!

Ritschl’s main teacher in Halle was Christian Karl Reisig but Reisig had died by the time he got his doctorate, so we will also need to trace back the lineage of his official sponsor, Moritz Meier. The story of Ritschl’s studenthood is well re-told by William Clark in his book “Academic charisma and the origins of the research university” on pages 230-237 (based largely on Ribbeck’s biography of Ritschl). Here’s the gist of it:

Ritschl started as a student in Göttingen in 1824, studied in Leipzig in 1825 and 1826, and then went to Halle. He had studied with Gottfried Hermann in Leipzig and then studied with Hermann’s student Reisig in Halle. Reisig was in a feud with Moritz Meier, who had been appointed director of the philological institute over Reisig’s head. That feud was in fact a continuation of a feud between Reisig’s teacher Hermann and Meier’s teacher Böckh. We will get back to this (a faint echo in the past of the sixties' Linguistics Wars?).

Reisig founded and ran a private society which was meant to be a rival to the official institute run by Meier. Clark picks up the story:

In Ritschl’s student days at Halle, public disputation enjoyed high esteem anew, especially among the classicists. Nonclassicists trembled when they faced classicists as opponents in disputation, still conducted in Latin. Internecine warfare between the classicists had arisen from the projection of the Hermann-Böckh feud into the camps of Reisig’s society versus Meier’s Greek section of the Halle seminar. Ritschl had transferred to Halle in 1826, the year after the Hermann-Böckh feud had become bitter. He soon made a name for himself as an opponent at disputation. He sought to annihilate students from the seminar’s Greek section – students, that is, of Böckh’s student Meier – in disputations.

In 1828, Heinrich Foss, the senior student in the seminar and a devoted disciple of Meier, wrote and tried to defend his doctoral dissertation. Foss himself had previously attacked a student named Wex from Reisig’s classics society at Wex’s public disputation. Ritschl sought to play the avenger by attempting to destroy Foss at Foss’s public disputation in 1828. Foss received his doctorate, but the disputational battle between him and Ritschl supposedly not only split the gown but also the town of Halle in two camps. “Even the ladies” of the town supposedly took sides in this doctoral drama.

After Reisig’s death, Ritschl was without a doctor father. But Meier took the high road and took him under his wings. He even said that if Ritschl could get his doctorate and his habilitation before the fall of 1829, he would get him a job as a lecturer (Privatdozent). But this meant that Ritschl had to get two pieces of written work done by the fall. So, he did what every good student would do: procrastinate. In the end, a heroic effort got everything done just in time:

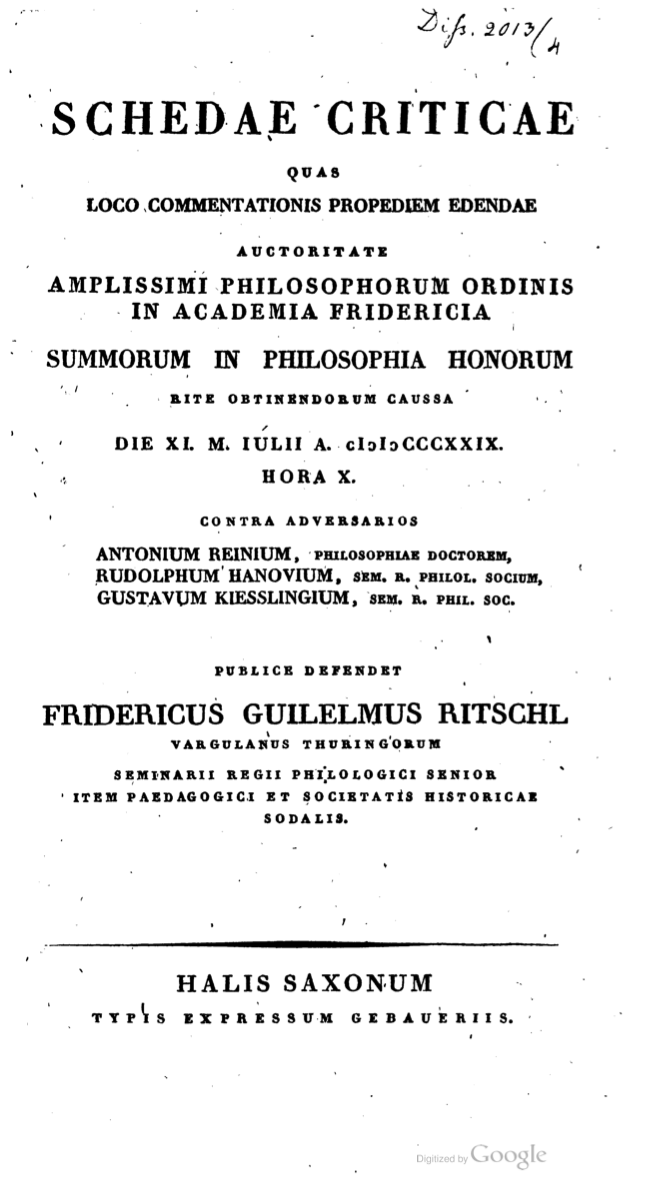

he spent three days, with a total of nine hours sleep, shaping the emendations into a coherent dissertation. He then paid for three typesetters to work through two nights to get the dissertation printed on time – the printer probably had other obligations for the normal day hours. “This was the thing composed, set, printed, and bound at night – a true work of the the night.” But it was done. He did the theses the night before the disputation. After two hours sleep, he appeared at the public disputation at 10:00 a.m. I do not know if any of Meier’s seminar students tried to annihilate Ritschl. But, by 3:00 p.m., 11 July, after five days labor with little sleep, a new doctor of philosophy existed.

Here is the title page of the dissertation, which is available from the Bavarian State Library:

I already mentioned that there will be more to say about the Hermann-Böckh feud. But clearly, bad blood arose easily in those days. Ritschl was the central party in the so-called “Philology War of Bonn”. The gist: Ritschl wanted to hire an additional faculty member to strengthen classical philology in Bonn when his colleague Welcker was getting on in years. He chose Otto Jahn and got him hired without Welcker’s knowledge, while Welcker was abroad on sabbatical. Welcker wasn’t all too thrilled when he found out. Jahn tried hard to become Welcker’s friend, which angered Ritschl. Years later, Jahn tried to get his friend Hermann Sauppe hired, this time behind Ritschl’s back. Sauppe in the end didn’t accept the offer, but Ritschl went ballistic and started a campaign against Jahn. Ritschl was reprimanded by the ministry of education, the press got riled up, the parliament discussed the case. Fun and games. In the end, Ritschl left Bonn to take a position in Leipzig. Soon though, Bücheler and Usener restored Bonn Philology to its leading status.

In the next installment, I will talk about Ritschl’s teachers Meier and Reisig, and their teachers Hermann and Böckh. Reisig, by the way, is often mentioned as the first philologist to take semantics seriously, under the term “Semasiology”, which he coined.

← Outreach Language Science Press →