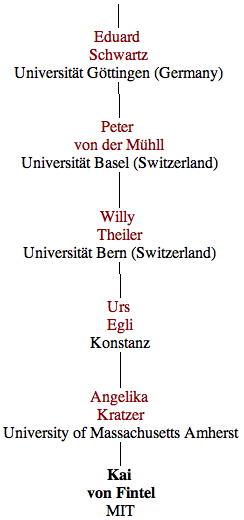

I received my PhD from UMass in 1994 with a dissertation called “Restrictions on Quantifier Domains”. I started teaching at MIT in 1993 and was finishing my dissertation during my first year of teaching here. My dissertation advisor (Doktormutter, “doctor mother”) was Angelika Kratzer. There were other very strong influences, of course, chief among them Barbara Partee, but for the purposes of the tree I will go by formal dissertation advisor relationships where possible. I will find some other occasion to talk more about my own intellectual biography and research career.

Angelika Kratzer

There are many ways in which Angelika was the perfect doctor mother for me. But one aspect I want to highlight here is that just like me, she has a passion for the history of our field. Her dissertation abounds in historical connections, one of which that struck me early on was the emphasis on the contributions of John Wallis [If you’re interested in this kind of thing, John Wallis appears as a character in a fun novel: “An Instance of the Fingerpost”]. This kind of historiographic interest was something I just soaked up. One of my early encounters with semantics, in fact, was a seminar taught by Professor Schepers of the Leibniz Research Institute in Münster on medieval semantics (William of Sherwood, William of Ockham, etc.) and other classes like that. For example, I learned to read Aristotle in the original and wrote one of my first college-level term papers on the notions of contradiction and contrariety in Peri Hermeneias (using not just the original but also medieval Arabic commentaries thereon).

Angelika wrote her dissertation entitled “Semantik der Rede: Kontexttheorie – Modalwörter – Konditionalsätze” doi:2027/mdp.39015015396008 in 1978. Her official advisor at the University of Konstanz in Germany was Urs Egli. I will not expand on Angelika’s intellectual biography, something she has already sketched on her website. Here’s an excerpt:

“I wasn’t born to become a professor. The town I grew up in didn’t have a high-school for girls. Girls went to a Middle School run by nuns, learned cooking and bookkeeping, and got married. The next town over did have a high school for girls, but it only had a Modern Language track. The boys’ high school there had Modern Languages, too, but there also was a Science and a Classics branch. For reasons that nobody could remember any longer, the Classics track took in a few girls every year. I was one of them, and nine years of Latin and six years of Greek - six days a week - must have turned me into a linguist. I discovered modern linguistics when I tried to find a way to combine my love for the shape of languages and mathematics, and discovered the close-to-Utopian Linguistics Department in Konstanz after getting lost at the traditional University of Munich and taking a year off as an assistant teacher at the Lycée Jean Dautet in La Rochelle (France). I cobbled a graduate education together for myself via research assistantships and scholarships that took me to the University of Heidelberg and to Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand). Before coming to Amherst, I was a researcher at the Max Planck Institute in Nijmegen and taught at the Technical University in Berlin.”

[She further talks about] “a dream of a community of scholars that I myself was part of as a young student in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Konstanz, where Arnim von Stechow and Peter (Eberhard) Pause took me in as a colleague and friend, and where I first met Irene Heim, (Thomas) Ede Zimmermann, and my thesis advisor Urs Egli. Other academic teachers whose lectures and seminars left a mark on me include Peter Glotz (film and communication), Wolfgang Braunfels (history of art), Hans Rheinfelder (Dante), and Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, who was a guest professor at Konstanz for a semester.”

[About her dissertation she adds:] “From the time I started my dissertation work in New Zealand with the help of Max Cresswell, George Hughes, John Bigelow, and David Lewis, I have been interested in context dependent semantic phenomena, in particular tense, modals and conditionals. My dissertation Semantik der Rede (Semantics of Discourse) dates from 1978, but the questions I struggled with then are still very much alive these days, and I keep returning to them.”

Angelika has shared with me this picture taken after her dissertation defense:

Urs Egli

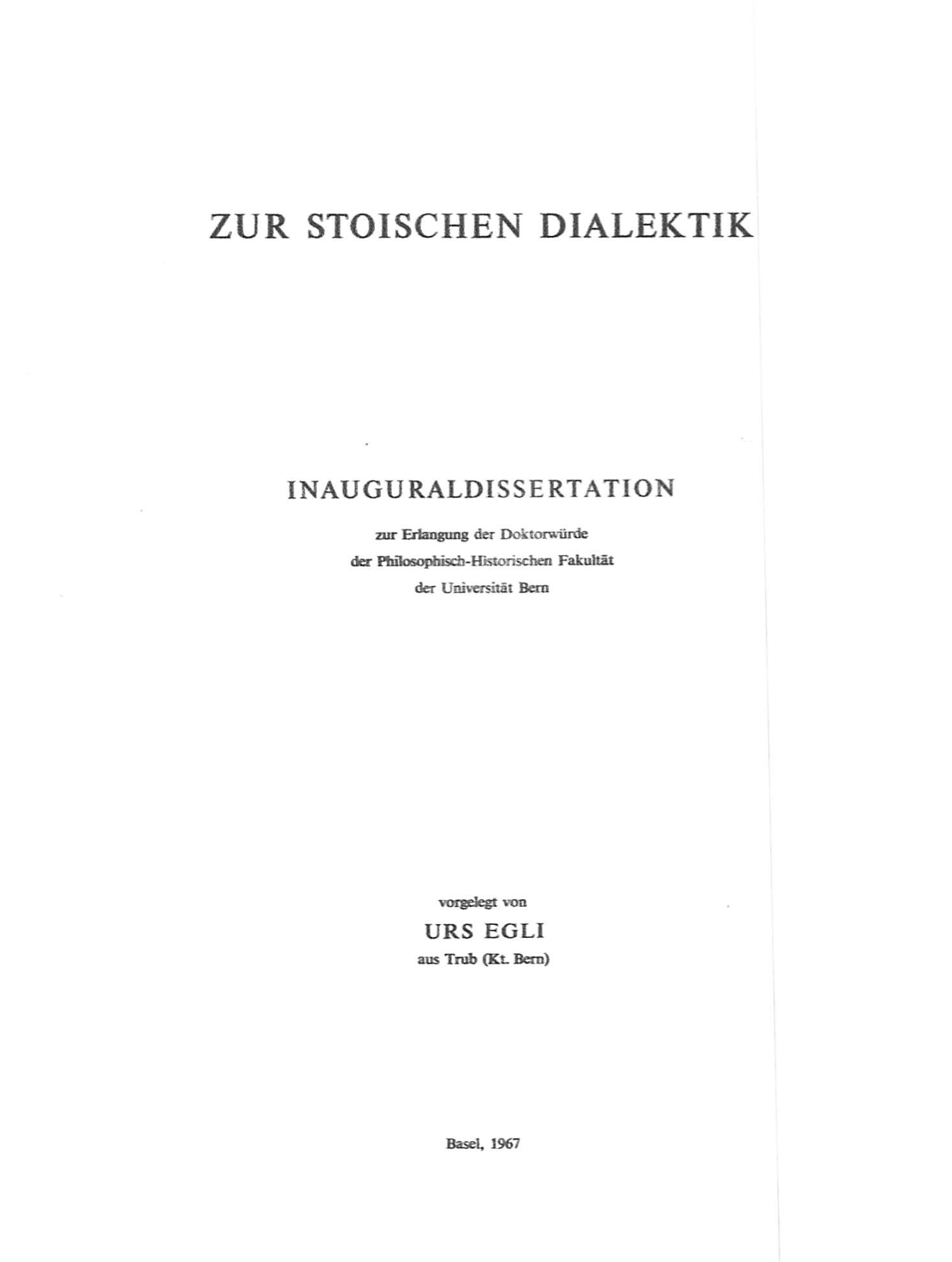

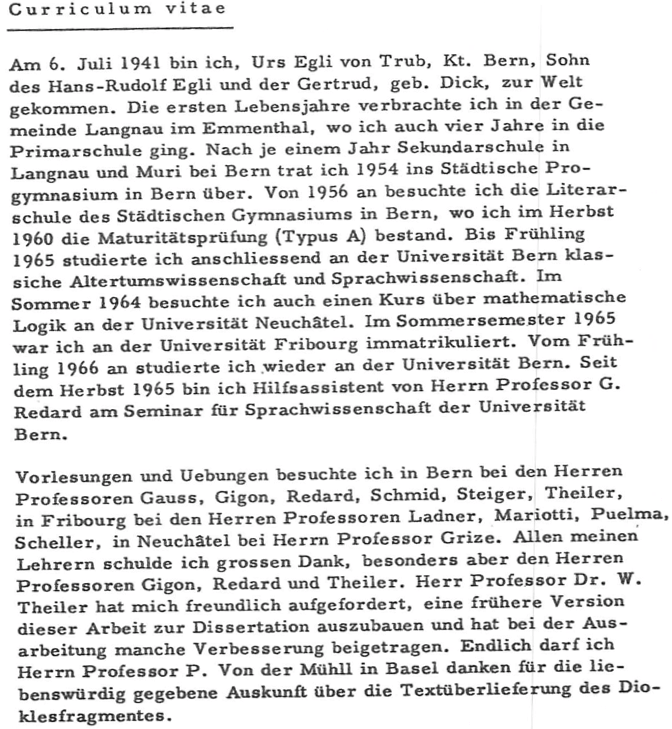

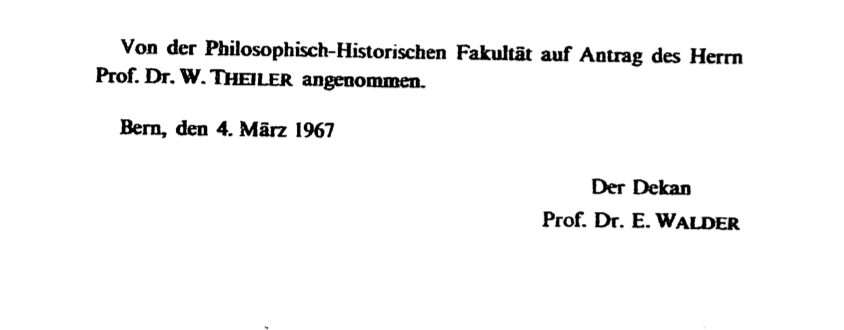

Urs Egli wrote a 1967 dissertation entitled “Zur stoischen Dialektik” at the University of Bern (Switzerland) under the direction of Willy Theiler. This information was a bit hard to find. I obtained an interlibrary loan copy of Egli’s dissertation and there is a page with a statement from Dekan (Dean) Prof. Dr. E. Walder that the dissertation had been accepted by the philosophical-historical faculty of the University of Bern at the request of Herr Prof. Dr. W. Theiler. I show here the title page, the decanal note, and the vita from the end of the thesis (a traditional component of doctoral dissertations).

An aside: A striking (mostly unsurprising) thing to see in Egli’s acknowledgments is that in his long list of professors whose lectures and seminars he attended, there is not a single woman. In fact, Angelika is not just the only woman in my entire tree, but there is no other woman to even be mentioned in the intellectual biographies of any of these men [this may not be strictly true, since it seems that Anna Comnena might be in the tree]. Our community has come a long way when I can honestly say that the four most important people in my immediate academic background are Angelika, Barbara, Irene, and Sabine.

When I first posted this first installment of my genealogy, I was contacted by Urs Egli and his wife, Renata Egli-Gerber. They shared with me a number of relevant materials, including a hard copy of Egli’s dissertation, some other writings, and an academic autobiography, which I can now make publicly available: “Wie man in Europa sowohl Altphilologe als auch Semantiker werden konnte”. For those who do not read German, here’s some highlights:

Egli entitles these memoirs: “How in Europe one could become both a classical philologist and a semanticist”. He was fascinated by Latin and Greek in school where he delved deep into grammatical and historical studies of those two ancient languages. He was also influenced early by the writings of Carnap, but it wasn’t possible to study mathematical logic or model-theoretic semantics in Bern, so after graduating from high school in 1960, he enrolled in General and Historical Linguistics and Greek and Latin, against the hopes of his high school teachers who thought he should study physics or “at least” biology. But his chosen disciplines offered at least a fail-save career option: he obtained a high school teacher’s diploma for Greek and Latin.

Around 1962, he discovered Chomsky’s “Syntactic Structures” in the university library and started thinking about ways to connect generative grammar, logic, and philology. He was a student of Georges Redard (a student of Emile Benveniste, in turn a student of Meillet’s, in turn a student of Saussure’s). Redard, though, wasn’t willing to advise a disertation on logic and formal grammar. So, what Egli finally settled on was a topic in the history of logical semantics (an area that he was drawn to through Bochenski’s work) and Willy Theiler in the same department as Redard agreed to advise the thesis. He wrote on stoic logic and semantics, combining logical analyses drawing on Mates and Lukasiewicz and philological work of Theiler, von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf, Eduard Schwartz, Fuhrmann, Kochalsky, and von der Mühll. The thesis was accepted in 1967.

Redard, who knew Chomsky from a summer school, wrote to Chomsky and helped Egli get an offer of a postdoctoral fellowship at MIT, but he couldn’t go there because of health reasons. (Egli adds that not going to MIT may have been a good thing because he suspects that at the height of the “linguistics wars”, he might not have thrived there, because of his tendency to try to give all approaches their due and to combine them where possible.) So, he went to Cologne to work with Hansjakob Seiler, the director of the linguistics department there (who was just about to retire when I myself started studying linguistics there in 1984 and who was replaced by Sasse, who I took several seminars from). While there, he discovered the third significant work that informed his career: Montague’s universal grammar (through Helmut Schnelle’s exposition). He wrote his “habilitation” (second dissertation to earn the right to be a professor) on Montagovian/Chomskyan themes. This time, Redard advised the work and Egli stresses that the combination of insights that he put together seems to him to realize one of Redard’s favorite aphorisms of Saussure’s: “la linguistique sera algébrique ou elle ne sera pas”. Indeed. In 1974, the philosophical-historical school of the University of Bern accepted the habilitation.

Egli says that apart from his official genealogy through Theiler, von der Mühll, Schwartz, which is what I will be tracing here, he has a second lineage through Redard (associating him with Max Niedermann, Jacob Wackernagel, Emile Benveniste, Antoine Meillet, and Ferdinand de Saussure). And then, obviously, there is the intellectual influence, which we all share, of Carnap, Chomsky, and Montague.

Willy Theiler

Willy Theiler (* 24. Oktober 1899 in Adliswil; died 26. Februar 1977 in Bern) taught at the universities of Königsberg (1932–1944) and Bern (1944–1968). Here’s a photo of him from an obituary article in the journal Gnomon:

Theiler’s dissertation “Zur Geschichte der teleologischen Naturbetrachtung bis auf Aristoteles” was filed at the University of Basel (also Switzerland) in 1924 (at the age of 25) under the direction of Peter von der Mühll. A later edition is in fact dedicated to von der Mühll.

According to Theiler’s obituary, von der Mühll was an extraordinary teacher whose seminars attracted many young scholars over the years. Even though there were 43 years between Theiler’s dissertation and Egli’s dissertation, Egli writes in his acknowledgments that von der Mühll had helped him with some information about manuscript transmission. Theiler supervised 26 dissertations (and more at institutions other than the ones he was teaching at) over his career. He was an eminent philologist, specializing in ancient philosophy.

Peter von der Mühll

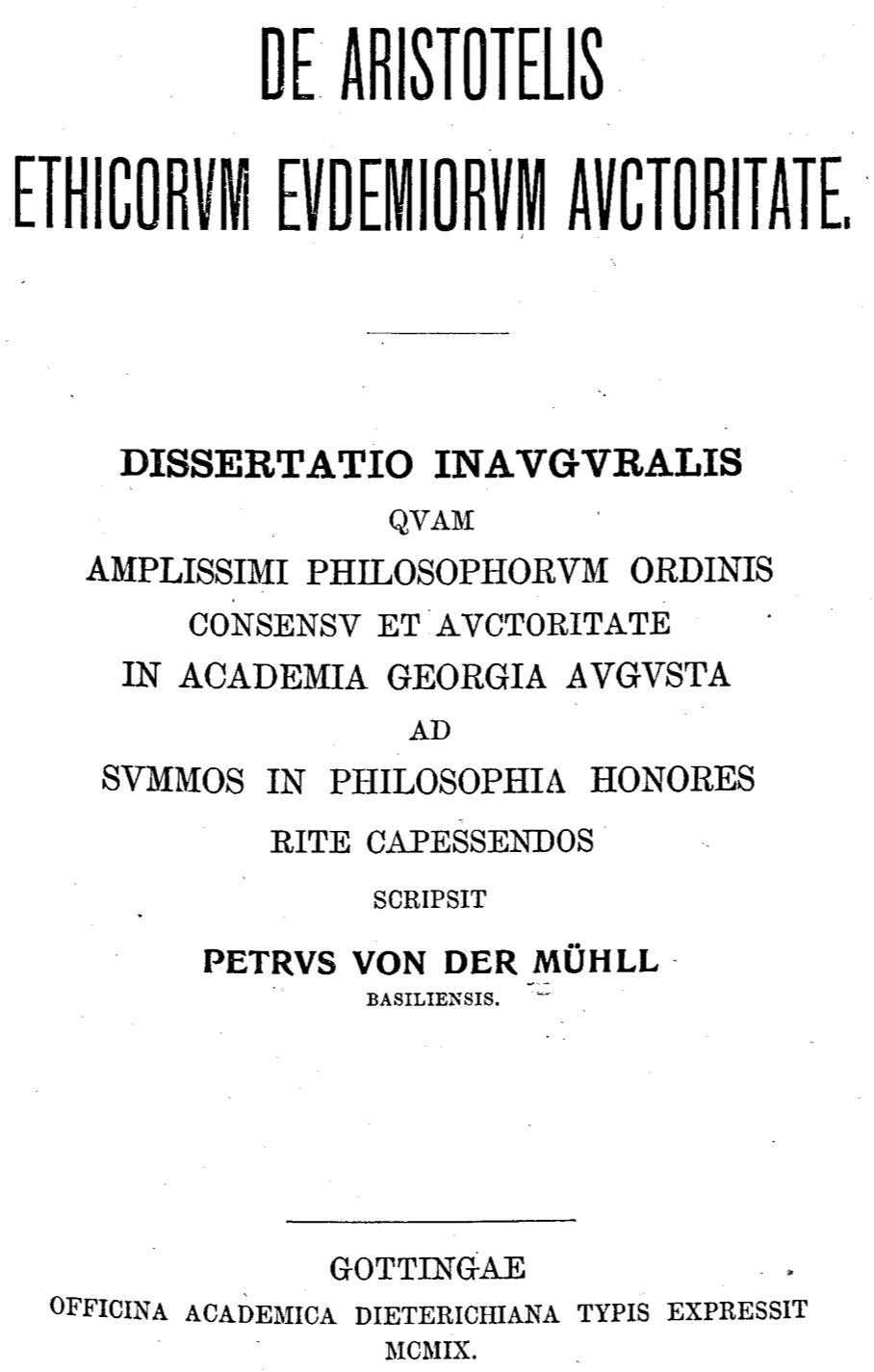

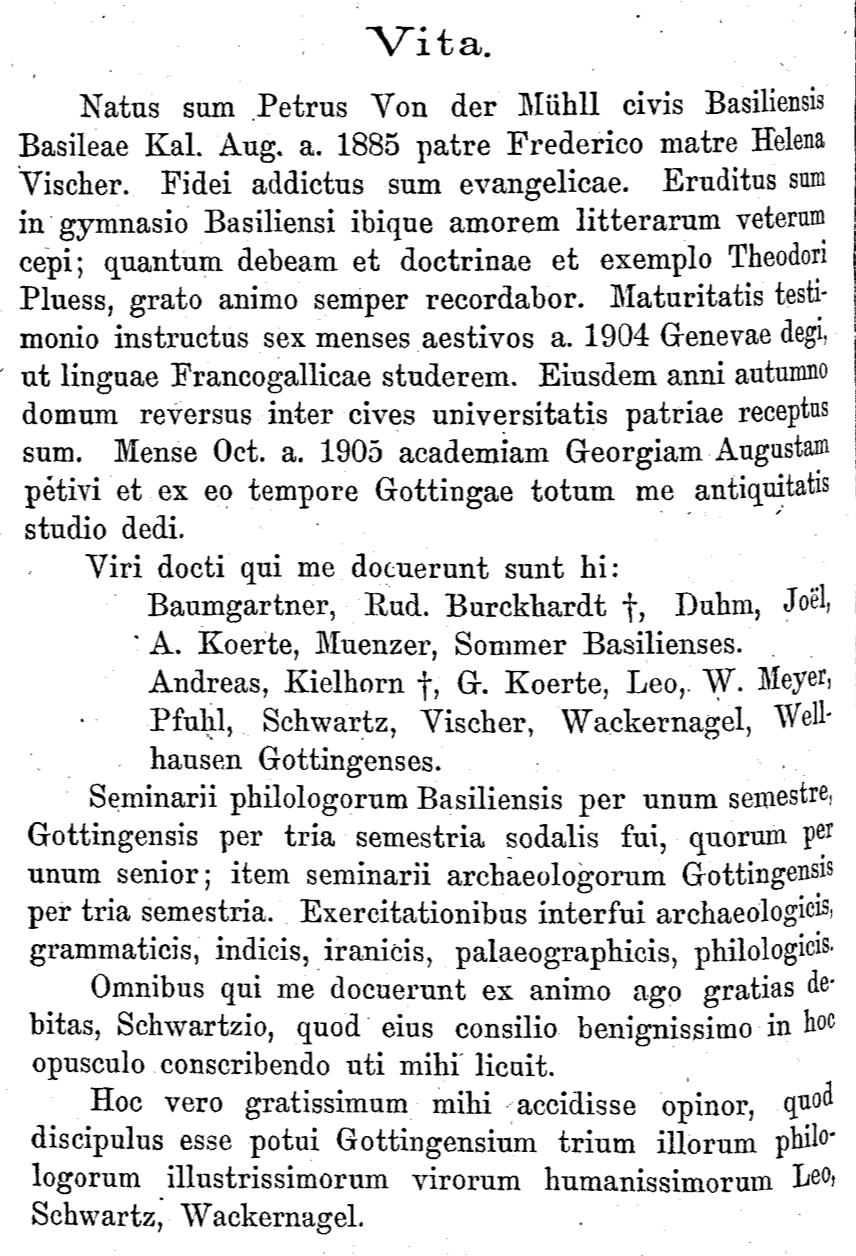

With Peter von der Mühll (* 1. August 1885 in Basel; died 13. Oktober 1970 also in Basel), the tree leaves Switzerland; he was Swiss and taught at Zürich and Basel, but he got his doctorate in Göttingen (Germany) in 1909 (at the age of 26) with a dissertation entitled “De Aristotelis Ethicorum Eudemiorum auctoritate” under the direction of Eduard Schwartz, who together with Jacob Wackernagel and Friedrich Leo made Göttingen a center of excellence in classic studies. From now on in the tree, all dissertations were written in Latin. This one is a mere 47 pages long and it has a DOI: 2027/uc1.b2619343. Unfortunately, Google’s scan of the last page of the dissertation, which has a Vita including acknowledgments, is a bad scan cutting off the right side of the text, so it’s not really useful, except that one can see that he acknowledges Wackernagel among others. So, I obtained a fresh scan from Harvard’s Widener Library. I am posting a four page excerpt with the title, dedication, and Vita pages.

Von der Mühll didn’t publish all that much in his career, focusing on his teaching, advising, and on administrative duties (he was rector of the University of Basel for a while). Here’s a photo (again from an obituary article in Gnomon):

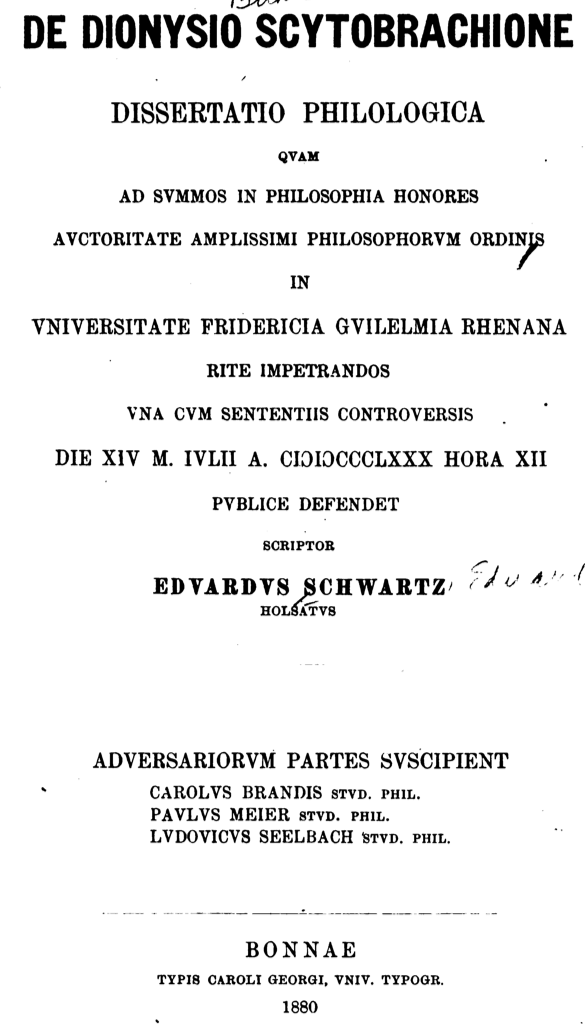

Eduard Schwartz

Eduard Schwartz (* 22. August 1858 in Kiel; died 13. Februar 1940 in München) was mainly trained at the University of Bonn (when I lived in Cologne and regularly visited Bonn, the Intercity trains used to announce that Bonn was the birth place of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven and the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany … in that order).

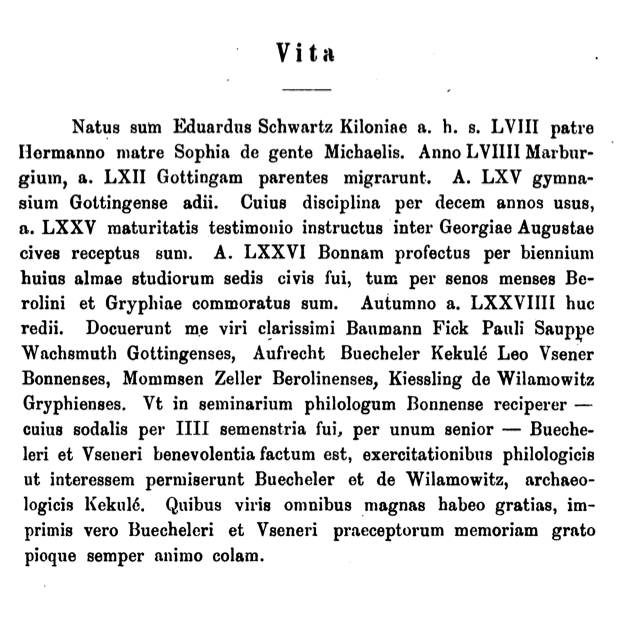

He received his doctorate there with a dissertation entitled “De Dionysio Scytobrachione” (freely downloadable as a pdf from Google Books) in 1880 (at the age of 22; note that the ages at which these academic ancestors got their degrees are decreasing as we go back in time, indicating how professionalized the discipline has become over time). His co-advisors were Franz Bücheler and Hermann Usener. His dissertation has a list of 11 controversial theses at the end (a feature you can still see in linguistics dissertations from the Netherlands, and which recurs in the dissertations further up the tree). The title page lists three fellow students who served as the disputants at the defense (again, a traditional component of doctoral dissertations for a while). His doctorfathers are acknowledged on the next page in the dedication, and his vita contains a list of other teachers.

[To be continued]

← When you know you’re a geek News from the open access revolution →